Peggy and Victor are competing on who can solve a certain Sudoku puzzle the fastest. Sudoku rules: fill a nine-by-nine grid with digits, such that each column, each row, and each of the three-by-three subgrids – called boxes – contains each digit from 1 to 9 exactly once. After racking her brain for hours, Peggy finds the solution – and she's first! Now, she wants to prove to Victor that she has indeed solved the Sudoku. Peggy is a good sport, and she doesn't want to ruin the puzzle for Victor. This means that she cannot just show the solution to Victor. Peggy appears to be in a pickle.

Luckily, Peggy has recently heard of Zero-Knowledge Proof Systems. They seem to be the perfect solution to her problem. Peggy and Victor can use the card-based zudoku to convince Victor that Peggy knows the solution – and Victor won't get any hint about the solution. Peggy is in the role of the Prover: she proves she knows the solution. Victor's role is called Verifier, since he checks whether Peggy really knows it. These roles appear in every Zero-Knowledge Proof System, not just zudoku.

zudoku is immediately useful in proving knowledge of Sudoku solutions – obviously a very common problem. Apart from that, it demonstrates that Zero-Knowledge technology is not (necessarily) magic. zudoku is very intuitive and doesn't need any mathematics or programming.

zudoku

The zudoku proof system is an interactive protocol. Zero-Knowledge + Sudoku ⇒ zudoku That means Peggy and Victor have to play together for the entire thing to work.

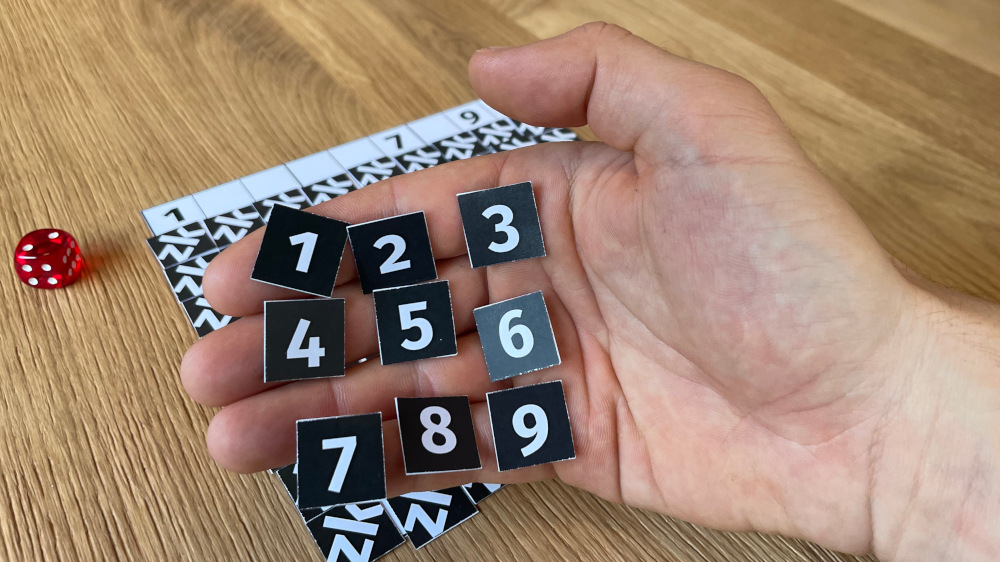

Furthermore, Peggy needs some cards, all with the same back side. The front of a card shows one of the digits 1 through 9. Because Peggy will lay out her solution using the cards, she needs nine cards per digit.

Lastly, Peggy and Victor need the Sudoku puzzle they are playing zudoku with. Victor has printed the puzzle and puts it before them. Printing the puzzle is not necessary. It just makes playing zudoku more convenient.

setup

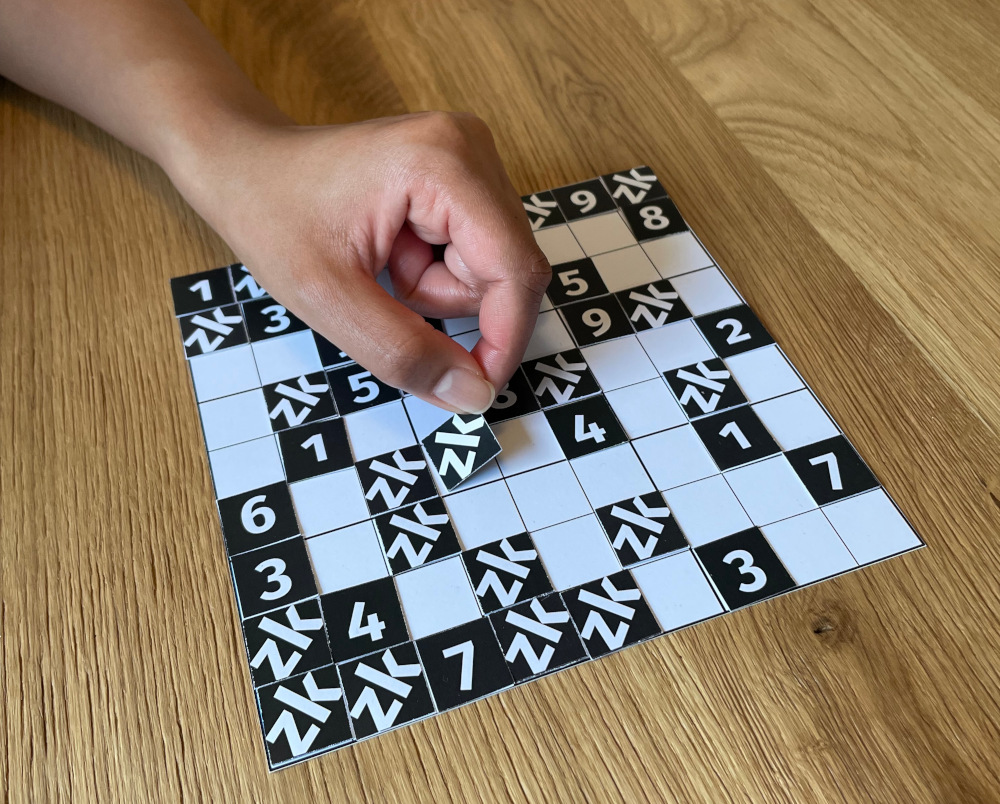

Peggy and Victor start with the setup for zudoku. They use Peggy's cards to mimic the puzzle: every digit printed on the grid is covered with a card showing the same digit, with the digit facing up.

When all printed digits are covered, the Sudoku essentially still looks the same, except that instead of Victor's print-out, Peggy's cards are used. This is why printing the Sudoku is not necessary – laying out the puzzle using the cards is enough.

commit

Peggy puts the solution with her cards facing down into the free cells. She needs to make sure that Victor can't tell which card she puts where – otherwise she would be giving him hints!

challenge

Now it's Victor's turn. Theoretically, he could just turn all or some cards around – but that way he'd learn something about the solution! Instead, Victor chooses whether he wants to check the Sudoku's rows, or the columns, or the boxes. Ideally, Victor's choice is as random as possible, for example by rolling a die: rolling 1 or 2 means checking rows, 3 and 4 mean checking columns, and 5 and 6 mean boxes.

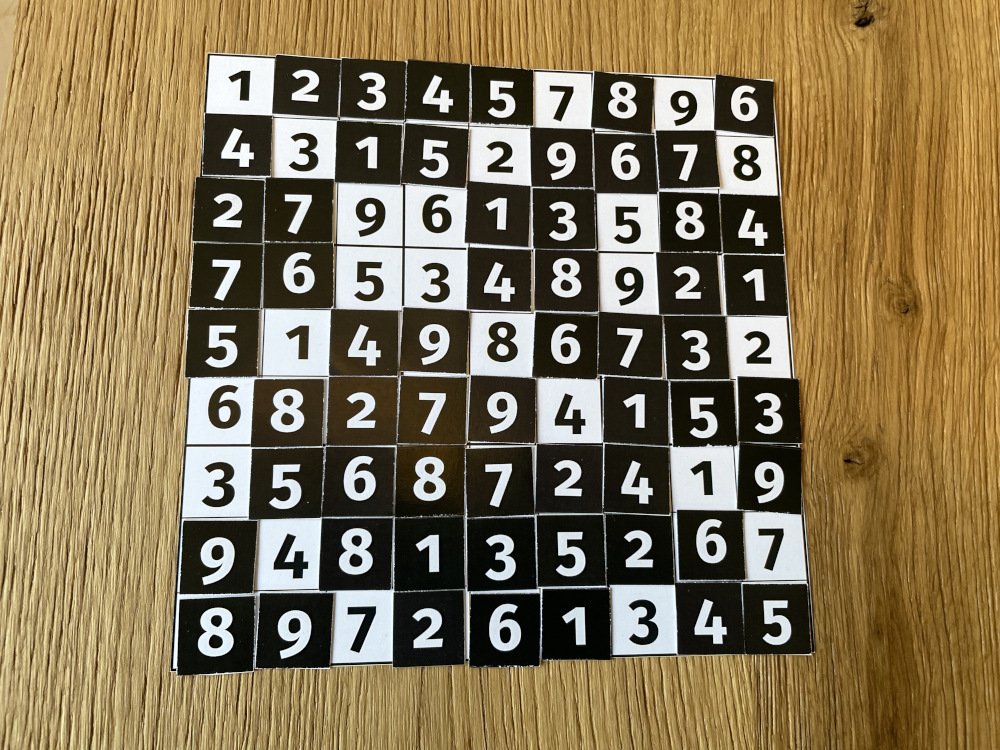

Victor chooses to check the rows. He takes all nine cards in the first row, shuffles them, and turns them around. Then he checks that all digits, 1 to 9, are there – none missing, none double. Since Peggy has put the correct solution for the Sudoku, this is exactly what he finds.

Shuffling the cards makes sure that Victor does not know the position of a card on the board. This way, even after turning the cards around, he doesn't know anything about the solution.

He proceeds to the next row, takes the cards, shuffles them, then turns them around. Again, he checks that the rules of Sudoku are followed – all digits appear exactly once.

This way, Victor checks all rows. It's very important that Victor sticks with his choice, and checks only rows, or only columns, or only boxes. If, for example, Victor were to check a column after having removed the first row, he would have only eight cards. One digit would be missing: the digit where the checked column and the first row intersect. This way, Victor gets a hint about the solution. If, in any row, he were to find some digit twice, he would know that the rules of Sudoku were violated – which would mean that Peggy did not actually put the solution in the board! But Peggy has put the real solution, so for every row, Victor finds every digit exactly once.

repeat

Even though Victor has confirmed that Peggy has put her cards in a way that the rows comply with the Sudoku rules, he is not convinced yet. After all, the rules of Sudoku apply to rows, columns and boxes, not just to rows! He tells Peggy that he wants to go again.

As before, they set up the Sudoku puzzle by placing cards face-up on the printed digits, and Peggy lays in the solution face-down again. Now, Victor can make the same choice as before: check the rows, or the columns, or the boxes. Again, he verifies that the chosen sections comply with Sudoku rules by shuffling the cards and turning them over.

If Victor is still not convinced, he asks Peggy to go again. And again. And maybe one more time?

Because Peggy always puts the correct solution, no matter whether Victors chooses rows, columns, or boxes, he will always find that the rules of Sudoku are upheld. After playing zudoku for enough rounds, Victor is finally convinced. A Zero-Knowledge Proof System where an honest Prover can always convince an honest Verifier is called complete.

But why can he be so sure that Peggy didn't cheat?

catching cheaters

The mischievous Mallory overheard Peggy and Victor perform zudoku. Mallory is not a great Sudoku puzzler, and she does not know the solution. However, she thinks that using zudoku, she can trick Victor into believing that she knows the solution.

Even though Mallory was not able to find the Sudoku's correct solution, she did prepare three “fake solutions.” These fakes are crafted in an attempt to fool Victor.

In Mallory's first fake, every digit appears exactly once per row, and also exactly once per column, but the boxes are all wrong.

The other two fakes are similar: in the second one, every digit appears exactly once per column and per box, but some digits appear twice or more in the rows. The third fake has inconsistent columns, but the rows and the boxes are fine.

Mallory and Victor start playing zudoku. First, they perform the setup. Now, Mallory needs to choose which of her fake solutions she wants to use. She picks the fake where the rows and the columns are fine, but the boxes aren't, and puts the cards face-down in the grid. Then she turns all remaining visible digits around.

Victor can now choose whether he wants to check rows, columns, or boxes. His decision is independent of Mallory's choice.

If Victor chooses to check the boxes, he will immediately realize that Mallory is cheating, call her out on it, and stop playing zudoku with her. Should he instead choose to check the rows or the columns, he won't catch her in this round. But no matter his choice, Victor is not convinced after just one round, so he asks Mallory to play again. If they play for long enough, it is very likely that Mallory is caught. After n many rounds, the probability that cheating Mallory is caught is 1 - (⅔)n. For 4 rounds, that's 80%. 10 rounds gives over 98%.

After all, Mallory has to guess which section Victor will not check before knowing Victor's choice. A Zero-Knowledge Proof System where a dishonest Prover can almost never convince an honest Verifier is called sound. In fact, probably even Victor himself doesn't yet know what he will check, especially if he is rolling a die! Once Mallory has made her guess, she cannot change the cards on the grid anymore – she is committed. Correctly predicting Victor's choice – or the die – many times in a row is quite unlikely. Technically, because there's a slim chance that Mallory is never caught cheating, zudoku is an Argument System, not a Proof System.

credits

zudoku is based on this paper.

Ronen Gradwohl,

Moni Naor,

Benny Pinkas,

and Guy N. Rothblum:

“Cryptographic and Physical Zero-Knowledge Proof Systems for Solutions of Sudoku Puzzles”

It is essentially a card-based variant of Protocol 6.

The paper is a lot more explicit about the involved assumptions, and formally analyzes soundness errors.

It is a good start for further reading.

I first heard about the protocol presented here, as well as the name zudoku, from Jörn Müller-Quade, who introduced me to the marvelous world of crypto. “Crypto” means Cryptography.

The Sudoku that Peggy and Victor were competing over is “AI Escargot” by Arto Inkala. It is reproduced here with his friendly permission.

This website is hosted on GitHub Pages, statically rendered by Jekyll, and uses the Basically Basic theme with margin notes from Tufte CSS mixed in.